panorama destination

panorama destination

Sometimes a journey can be just as illuminating as the destination. On the road to Toraja, Sulawesi lays out a tapestry of landscapes and cultural clues; a trail of breadcrumbs leading us to the roof of the island. Driving up to the highlands from the coast lets you see the character of the landscape transform before your eyes, as lowland plains, freshwater lakes and rolling farmland slowly merge into mountains.

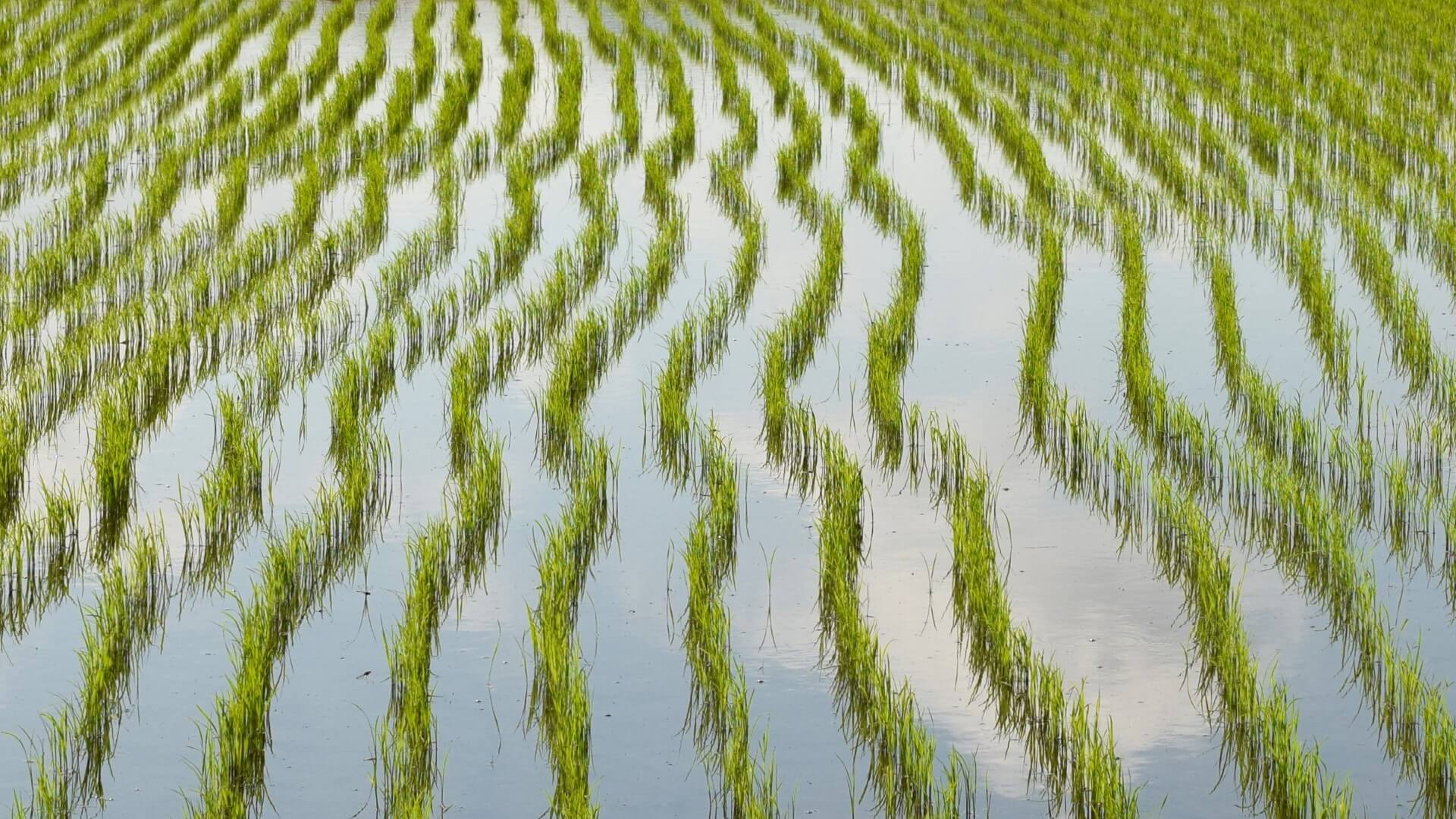

The road from Makassar is long, straight and smooth, plotting a course through a fertile plateau of fields. Flooded plains reflect the sky like a mirror, where farmers plough the land with buffalo and an endless panorama rolls past the window. Traditional homes on stilts, built in the Bugis style, are perched on islands in the flooded farmland. On their brightly coloured verandas, songbirds sing from wooden cages. Freshly harvested rice is drying in the gardens. Flustered hens and their little convoy of fluffy yellow chicks scratch in the undergrowth. All around are palm trees and fishponds, where dragonflies flicker in the wildflowers.

Splitting the journey from Makassar to Toraja, an overnight stop in Sengkeng is a welcome break, but also an adventure in its own right. Located roughly seven kilometres from the town centre and towards the edge of the River Walanae, Lake Tempe covers an area of 13,000 hectares and contains rare freshwater fish species found nowhere else. The lake is also home to floating communities of fishermen and their families; Bugis tribes from the coast who have migrated inland and found use for their mastery of the seas. These colourful atolls cluster together to form charming villages, where kids play in the water, teams of teenagers race their rowing boats and elders cast nets in search of fish. The only way to explore is by motorized canoe.

Every August, a sea festival called Maccera Tappareng is held at Lake Tempe. In an interesting link in the chain between coastal Bugis culture and the highland Torajans, the ritual is marked by the slaughter of cows. The festival also features traditional boat races, ornamental boat designs, traditional folk games, kite-flying competitions, traditional music performances and dancing.

“Solitary fishermen cast their nets beside towering palm trees jutting out of the water”

Sunset over the lake is an unforgettable sight. Solitary fishermen, silhouetted against the orange sky, cast their nets beside towering palm trees jutting out of the water. On the horizon, mountains are turning to hues of blue and lavender with the fading of the light. Darkness settles on Danau Tempe, but tomorrow is another day.

With the rising sun, our road continues up over bridges and rivers, where long wooden canoes pass by below. Like us, they are heading north, through the jungles and farms of the lowlands, onwards and upwards towards the mountains and into the realm of ancestors.

The first hint of Sulawesi’s mountain spine stirs into life as you reach the edge of Maros Regency. Limestone cliffs begin to emerge from the rice fields like dragon’s teeth. Draped in jungle foliage, they bake the air into little puffs of white cloud - a soft crown of cotton, spiraling skywards alongside egg-white egrets in the thermals.

The road begins to wind and pitch, buckling upwards as the landscape comes alive.

At Leang-Leang, an ancient seabed bursts through the soil like skyscrapers. Gnarled and twisted rock formations cluster like druids in this prehistoric valley; a former seabed, now turned to fossil and shipwrecked amongst the green.

The rocks here are older than humanity. Bookending the valley, towering limestone cliffs harbour secrets of our species’ arrival in the region around 50,000 BC. There are cave paintings, bones, tools, hearths and homes built into the rock; a tantalizing glimpse into the lives of early humans here.

Painted handprints on walls at the entrance to the cave look as though they could’ve been made yesterday. Like finger paintings hanging on a fridge, these colourful and tangibly personal artworks hint at the family who once made this cave a home.

“the oldest hand stencil in the world”

The sensation of time travel at Leang-Leang’s caves is so vivid that it feels a little like you are trespassing; as if some Neolithic hunter-gather dressed in animal skins will arrive at any moment, wondering why you are in his house.

The feeling is deceptive. In October 2014, an expert from Griffith University in Queensland, carbon dated the drawings and stated that the minimum age for the outline of the hand was 39,900 years old, making it the oldest hand stencil in the world. Next to it, in crimson ochre, is the torso of pig that has been dated to at least 35,400 years old, making this is one of the oldest figurative depictions in the world, if not the very oldest.

The captivating cave paintings of Maros regency not only give us a glimpse back in time to our distant ancestors, they also provide us with the earliest known examples of characteristics so quintessential to modern humans; creativity, consciousness and a compulsion to mark our existence in the world. To freeze and fingerprint our moment in time. They, like us, seemed compelled to say simply: “I was here.”

“ancient cliffs illuminated by a constellation of fires and the sound of music”

Thousands of years ago this landscape would have been a rich and fertile larder; a stream provided fish and fresh drinking water, whilst the fields all around would have made willing seedbeds for newly domesticated crops. The mountains overlooking the landscape are known to have at least 240 formerly inhabited cave sites – most of which remain unexplored. It is tempting to imagine the area as one of the world’s first cities; to picture those cliffs illuminated by a constellation of fires and the sound of music and laughter echoing through the ancient darkness and across the valley below. In the extraordinary stencils and cave paintings at Leang-Leang in Maros Regency, the lives of our ancestors continue to echo through time.